If you are familiar with research behind educational reform movements, then you are aware that in order for change to occur and be sustainable, it must be systemic (Tyack & Cuban, 1995). Change that happens in a vacuum will not last (Fullan, 2007). Grassroots change can only go so far. Top-down change, well…I’m sure we’re all well aware about how that goes. My point is, in order to change to occur, and I’m talking about real educational reform, then all stakeholders must be part of the process from the very beginning. True reform is not about implementing policy, but rather it “means changing the cultures of classrooms, schools, districts, [and] universities” (Fullan, 2007, p. 7). When considering educational reform issues such as technology integration (my dissertation focus) or multicultural education (focus for my summer blog series), well then it’s even more important to look at the entire system. My limited knowledge of systemic change on a broad level prevents me from being able to offer much in that area. However, because I have been a classroom teacher for 23 years and have held various leadership positions both at the school and district level, I believe I can offer some suggestions on how to go about starting the process at the school site (more to come on that in subsequent blogs).

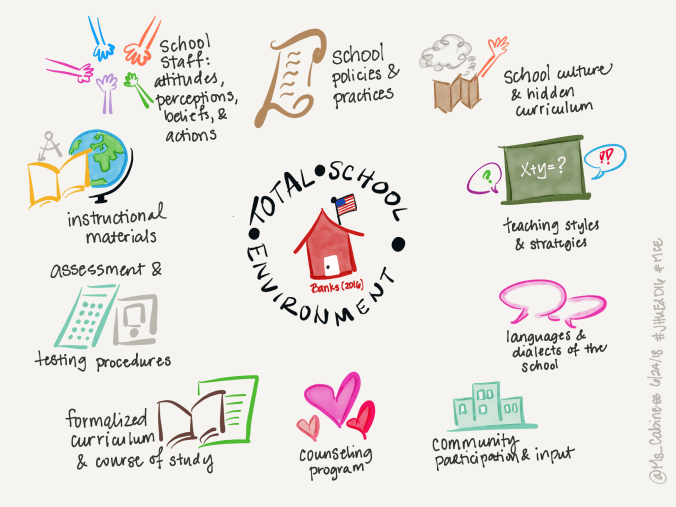

Multicultural education (as mentioned in a previous blog) has a variety of meanings which may differ depending on the organization. However, what one cannot deny is the fact that the definition of multicultural education is quite broad (Banks, 2016). As such, when considering what multicultural education looks like (or should look like) at a school, then one must begin by examining to what extent does the total school environment reflect monoethnic or monocultural practices of the dominant group (Banks, 2016; Nieto, 2008)?

The following image displays the elements that influence the total school environment (Banks, 2016):

Thus, when considering where to begin when integrating or implementing multicultural education, the answer is…everywhere. The process involves change across the total school environment. So, take a look at the sketchnotes to determine, where can you help influence the process? What other stakeholders do you need to include? How can you get them on the same page? Without a shared meaning or understanding of multicultural education across all stakeholders, believe me, your efforts will feel more like herding cats. And that’s a whole different profession.

References

Banks, J. A. (2016). Cultural diversity and education: Foundations, curriculum, and teaching (6th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Fullan, M. (2007). The new meaning of educational change (4th ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Nieto, S. (2008). Affirmation, solidarity and critique: Moving beyond tolerance in education. In E. Lee, D. Menkart, & M. Okazawa-Rey (Eds.). Beyond heroes and holidays (pp. 18–29). Washington DC: Teaching for Change.

Tyack, D., & Cuban, L. (1995). Tinkering toward utopia: A century of public school reform. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

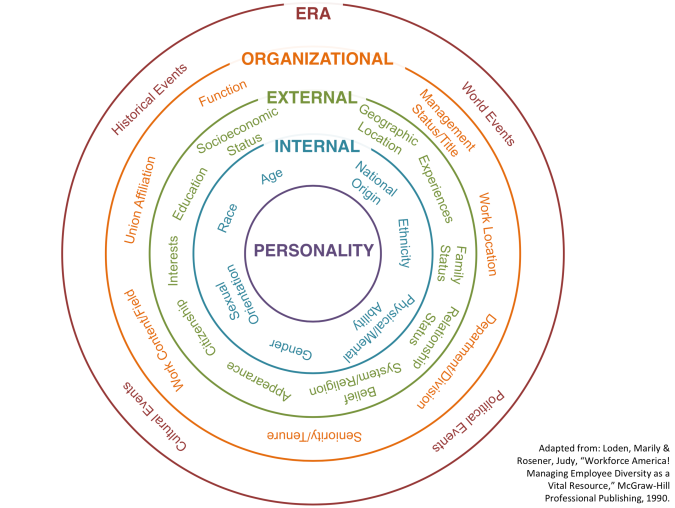

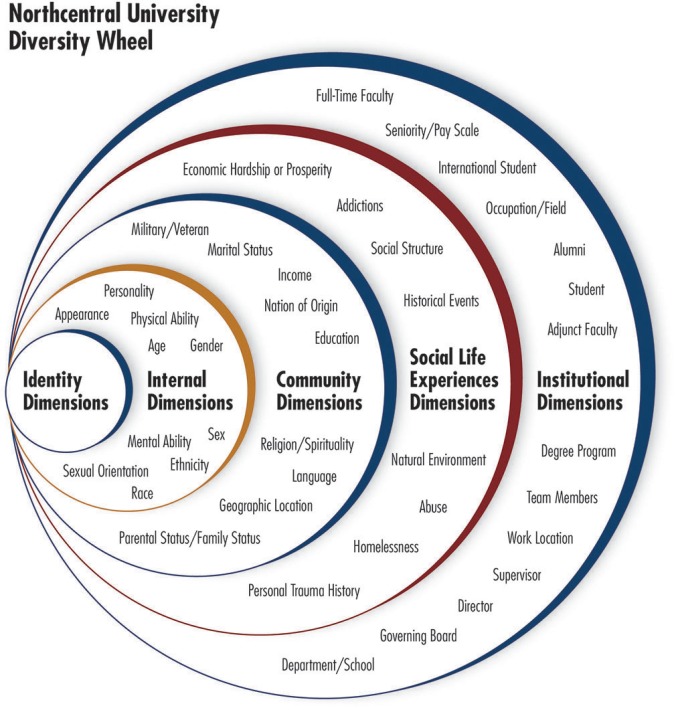

This diversity wheel aligns with Bronfenbrenner’s (1977; 1994) nested model of the ecological systems approach. In this case, the individual is the focal point from which radiates the varied types of influences upon the individual organized in concentric circles (from narrow to broad).

This diversity wheel aligns with Bronfenbrenner’s (1977; 1994) nested model of the ecological systems approach. In this case, the individual is the focal point from which radiates the varied types of influences upon the individual organized in concentric circles (from narrow to broad).